This page is part of the website www.donnan.eu. Return to Stuart Donnan's other personal writing here.

JOINING - FORM AND SUBSTANCE

THE FUTURE OF THE RELIGIOUS SOCIETY OF FRIENDS (QUAKERS) IN BRITAIN

a contribution by Stuart Donnan

THE FUTURE OF THE RELIGIOUS SOCIETY OF FRIENDS (QUAKERS) IN BRITAIN

a contribution by Stuart Donnan

SECTION 3

ONE THING IS MISSING (U) - BUT ANOTHER THING IS ALSO MISSING

RELATING TO QUAKER FORM AND SUBSTANCE

Back to top

ONE THING IS MISSING (U) - BUT ANOTHER THING IS ALSO MISSING

RELATING TO QUAKER FORM AND SUBSTANCE

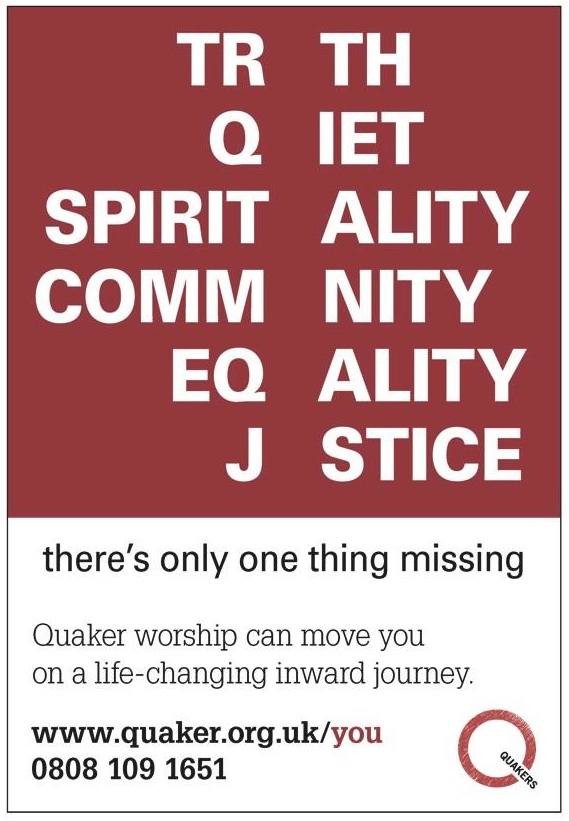

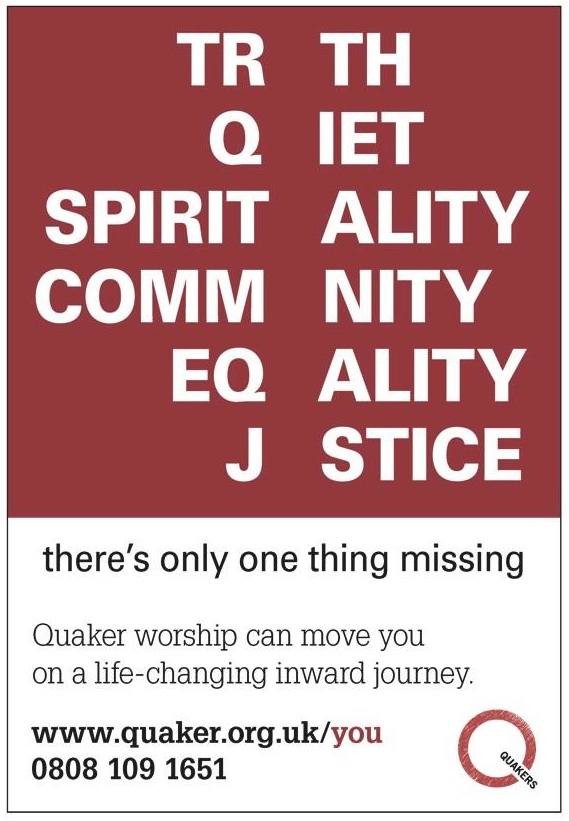

It is certainly true that U are missing and that message is now going out (including some parts of the 'secular' press).

JOINING seems a very appropriate idea for a Society concerned about creating community and creating connections. But the idea which often attracts the label of 'proselytising' is very foreign to most British Quakers. However John Stephenson Rowntree would have nothing of that attitude. In his essay he went so far as to call statements such as "we are not a proselytising people" pointless platitudes. He saw it as a failure that the Society of his time was "unsuited to be a direct agency even in the promulgation of its most prominent tenets".

But a Young Quaker writing in The Friend about Britain Yearly Meeting 2009 had clearly got the message: "I like that Quakers do not proselytise or shout about their good work, but when we take momentous decisions or when we're campaigning on really important issues, shouldn't we attempt to make our voices heard?" And he even felt guilty for thinking that the same-sex marriage agreement would "boost the profile of Quakers" when the Friends House media relations team were publicly "chastised" for using the term 'Quaker brand'. The young John Wilhelm Rowntree might have had a retort for that crusty rebuke.

Is diffidence a problem? A survey of attenders (admittedly more than 20 years ago, as reported by Heron) saw Quakers as tending to be diffident and as seekers rather than finders; they were also thought to be poor communicators at a personal face-to-face level on matters of faith and experience (and diffidence is understandable as part of that).

This attitude may seem very British - it's not how African Quaker churches were planted by North American missions - but our Framework for Action prominently quotes (and thus promotes) the words of an American Friend (with my emphasis): "To this day Friends everywhere disdain pressing their faith on others, preferring them to be led by the Spirit." Disdain! Being hyper-charitable and trying to allow for transatlantic differences in vocabulary, this reader still finds it extraordinary that the only alternative to being "led by the Spirit" (in a vacuum?) is portrayed as "pressing faith" - and in any case, is that to be condemned, never mind treated as contemptible?

Writing in The Friend recently, the partner of an enquirer (the partner being a church member) showed true Quaker hesitation and meekness: "It mystifies me that, in a world where many people are looking for a cause or faith to espouse, having been disenchanted by the established church, Friends hide their light rather than being open and proactive about their core values and testimonies. I understand that proselytising is not the Quaker style but at the risk of giving offence I dare to ask why?" Struggling for an answer to her own question, she continues with disarming, even devastating turns of phrase: "Is there perhaps some vested interest in remaining a small and almost exclusive minority group? What other reason could you have for not wooing the disillusioned or the unchurched when you have so much to offer?" Now there's a word for Quakers to add to our vocabulary about outreach - "wooing".

Convincement is an old word, perhaps out of fashion in concept not just vocabulary. There may often be a genuine but mistaken apprehension that outreach - and the assumed in-drag that follows - can only be perceived by the outsiders as driven by dogma and the need for assent. Surely the removal of that misperception lies squarely in the hands of the Society.

Recent Quaker outreach, such as that with which this section began, seems to have avoided inviting misapprehension of this sort. But the question remains - what is the substance of the Quaker way which outsiders are to be asked to join? A brief excursion into 'notions' is necessary as we proceed to try to answer that question.

JOINING seems a very appropriate idea for a Society concerned about creating community and creating connections. But the idea which often attracts the label of 'proselytising' is very foreign to most British Quakers. However John Stephenson Rowntree would have nothing of that attitude. In his essay he went so far as to call statements such as "we are not a proselytising people" pointless platitudes. He saw it as a failure that the Society of his time was "unsuited to be a direct agency even in the promulgation of its most prominent tenets".

But a Young Quaker writing in The Friend about Britain Yearly Meeting 2009 had clearly got the message: "I like that Quakers do not proselytise or shout about their good work, but when we take momentous decisions or when we're campaigning on really important issues, shouldn't we attempt to make our voices heard?" And he even felt guilty for thinking that the same-sex marriage agreement would "boost the profile of Quakers" when the Friends House media relations team were publicly "chastised" for using the term 'Quaker brand'. The young John Wilhelm Rowntree might have had a retort for that crusty rebuke.

Is diffidence a problem? A survey of attenders (admittedly more than 20 years ago, as reported by Heron) saw Quakers as tending to be diffident and as seekers rather than finders; they were also thought to be poor communicators at a personal face-to-face level on matters of faith and experience (and diffidence is understandable as part of that).

This attitude may seem very British - it's not how African Quaker churches were planted by North American missions - but our Framework for Action prominently quotes (and thus promotes) the words of an American Friend (with my emphasis): "To this day Friends everywhere disdain pressing their faith on others, preferring them to be led by the Spirit." Disdain! Being hyper-charitable and trying to allow for transatlantic differences in vocabulary, this reader still finds it extraordinary that the only alternative to being "led by the Spirit" (in a vacuum?) is portrayed as "pressing faith" - and in any case, is that to be condemned, never mind treated as contemptible?

Writing in The Friend recently, the partner of an enquirer (the partner being a church member) showed true Quaker hesitation and meekness: "It mystifies me that, in a world where many people are looking for a cause or faith to espouse, having been disenchanted by the established church, Friends hide their light rather than being open and proactive about their core values and testimonies. I understand that proselytising is not the Quaker style but at the risk of giving offence I dare to ask why?" Struggling for an answer to her own question, she continues with disarming, even devastating turns of phrase: "Is there perhaps some vested interest in remaining a small and almost exclusive minority group? What other reason could you have for not wooing the disillusioned or the unchurched when you have so much to offer?" Now there's a word for Quakers to add to our vocabulary about outreach - "wooing".

Convincement is an old word, perhaps out of fashion in concept not just vocabulary. There may often be a genuine but mistaken apprehension that outreach - and the assumed in-drag that follows - can only be perceived by the outsiders as driven by dogma and the need for assent. Surely the removal of that misperception lies squarely in the hands of the Society.

Recent Quaker outreach, such as that with which this section began, seems to have avoided inviting misapprehension of this sort. But the question remains - what is the substance of the Quaker way which outsiders are to be asked to join? A brief excursion into 'notions' is necessary as we proceed to try to answer that question.

Back to top