I wish now to turn to the English title of this lecture — taken from Renée Fox, who was part of Robert Merton's team of social scientists who published some of the first studies of the sociology of medical education in 1957. She discussed three aspects of uncertainty to which I wish to add two. So I will now ask you to consider with me five aspects of uncertainty for us as medical students and teachers and as medical consumers in Hong Kong.

First, uncertainty for medical students and for doctors and society as a whole arises from limitations in current medical knowledge about the nature and causes of diseases and other health problems. This leads me to a consideration of some of the history of medicine especially as it relates to public health or social medicine or community medicine.

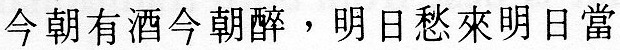

The writings of Huang Ti, the famed Yellow Emperor, come from the first century or two BC. His treatise,

The Yellow Emperor's Classic of Internal Medicine, contains a philosophy of living correctly and of maintaining health - hence the importance of prevention. As in the West, there was concern to minimize uncertainty: "The most important requirement of the act of healing is that no mistakes or neglect occur. There should be no doubt or confusion." I will now move ahead more than a millennium to mention some of the great men in the development of modern epidemiology - and return to the ancients later.

In the seventeenth century Bernardino Ramazzini became the father of one aspect of community medicine, namely occupational health, He took a broad view of causation of disease and said, "It is hardly ever possible to give any remedies that would completely restore health - for they suffer from yet another drawback - I mean they are very poor." He was writing of the working classes in seventeenth century Europe, but it was not only the poor who suffered from preventable diseases.

I have no time today to consider alcohol-related diseases - but there is a pub in soho in London called

The John Snow, one of a very few named after doctors. (One of the others is named after W.G. Grace who may be more familiar to some people!) John Snow was a doctor in London in the mid-nineteenth century - he was a man of many parts and popularized chloroform as a general anaesthetic, and helped legitimize anaesthesia during childbirth by giving chloroform to Queen Victoria at the birth of Prince Leopold.

Epidemiologists revere John Snow because of the Broad Street pump and the surrounding events. The pub is located in what is now Broadwick Street. Snow's map of Soho in the mid-nineteenth century shows the sweep of Regent Street and where Oxford Circus and Piccadilly Circus now stand, with numerous black spots representing deaths from cholera in one of the epidemics in the 1850s. In Broad Street there was a water pump and Snow suspected - although nothing was known about bacteria then - that the water was somehow involved. Two factors were especially important in having the decision made to remove the handle of the pump. First, a brewery stood nearby but there were no cholera deaths among the workers - it was said that they never drank water! The second factor was an isolated death from cholera in Hampstead; Snow discovered that the good lady used to live in Soho, and liked the flavour of the water from the Broad Street pump - so her son who worked nearby would bring her a bottle of the water back to Hampstead each day.

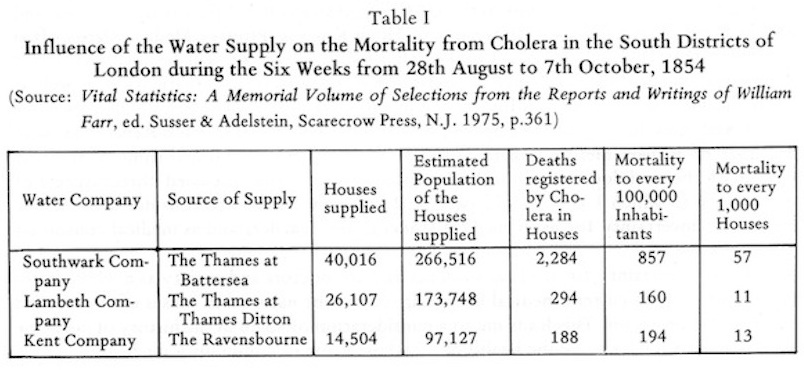

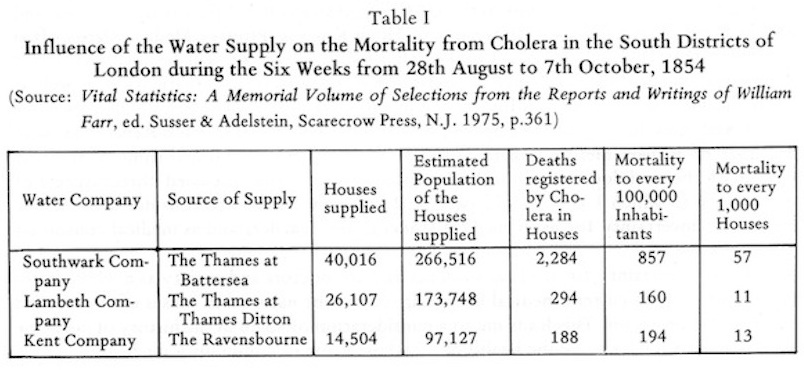

Around the same time it was noted that deaths from cholera in South London varied from place to place, Snow proposed what he called 'an experiment on the grandest scale' and walked from house to house in Southwark and Lambeth testing which water company supplied the water to adjacent houses. There was overlap in some streets as Snow's own map showed. He was able to rest for different mineral content - not of course for bacterial contamination. The Southwark water company took its water from the Thames near London Bridge. The Lambeth water company had moved its source up stream to near Twickenham and piped the water down. Table I shows the results of the grand experiment, indicating that water supply rather than location was a likely culprit.

This table was published by William Farr who was the first medical statistician at the General Register Office in London and a colleague of snow. He was a physician with a broad view and used his position to investigate with considerable ingenuity and originality the facts of life and death in Britain.

You will remember that these investigations of cholera pre-dated the discovery of bacteria, but not by much. The name of Pasteur is well-known to all, but the name of Robert Koch probably only to the medical people present. He was the father of modern pathology and is famous an his war on Tuberculosis - in relation to which he published his famous 'postulates' concerning the relationship of organisms and diseases:

Koch's Postulates (c. 1870)

- A specific organism must invariably be associated with all cases of the disease.

- The organism must be isolated in pure culture and then subcultured over repeated generations.

- When inoculated into a healthy susceptible animal, the organism must again cause the disease.

- The organism must again be isolated in pure culture from the lesions of the disease.

It is unfortunate that this work was essentially a laboratory exercise; although for laboratory pathology it is vital, it omits aspects of disease in the real world of individual people and social groups. ln particular, postulate (c) applies in selected laboratory animals but not in humans - I shall return to this in a moment.

John Ryle is something of a hero of mine - he was a physician at Guy's Hospital and the Ryle's nasogastric tube is named after him. He became Professor of Medicine at Cambridge and in the early 1940s moved to Oxford to become the first Professor of Social Medicine - much the same as what we mean by Community Medicine. One of his best known books is called

Changing Disciplines. His interests broadened from individual pathology to what he called 'social pathology' - which was not psychological medicine but concerned the relation of social and economic factors to the health of individuals and groups. In a much less exalted way I myself have followed Ryle's example of changing disciplines - it is about ten years since I left the Department of Surgery at Guy's.

ln 1942 Ryle wrote, "Various startling discoveries such as microbes and vitamins have brought about a tendency to neglect concomitant or primary causes, so that knowledge of the aetiology of disease has actually

suffered from the very discoveries which should have enriched it." Robert Koch was infected with the tubercle bacillus but did not develop the disease in the way his laboratory animals did - he died from a stroke at nearly seventy years of age and illustrated that there was much more to TB than the bacillus.

If we now consider health, as indicated by deaths, in Britain, McKeown has shown that the death rate dropped dramatically following the agricultural revolution and the industrial revolution despite pollution, crowding and so on. Food and its distribution were vital. For TB in Britain the death rate dropped by about one-half between the time when death registration began (1838) and the time when the tubercle bacillus was described (about 1880) and by another three-quarters before any specific preventive or therapeutic measures were available (in the 1940s). This applied not only to Britain but to many Western cities. In Hong Kong the toll of tuberculosis has likewise fallen although, as with newer and developing countries, the means of prevention and treatment have been available at the right time.

It is said that smallpox inoculation was known in China at about 1000 AD and also that poor quality rice was known at that time to be associated with beri-beri. This is one of the so-called vitamin deficiency diseases which, as Ryle pointed out, results not primarily from a deficiency of one of the B Vitamins but primarily from a deficient diet and inadequate food production and distribution. lt is also said that in the thirteenth century AD Peking had the best drainage system in the world, and that at that time even the common people when travelling took care to drink only boiled water!

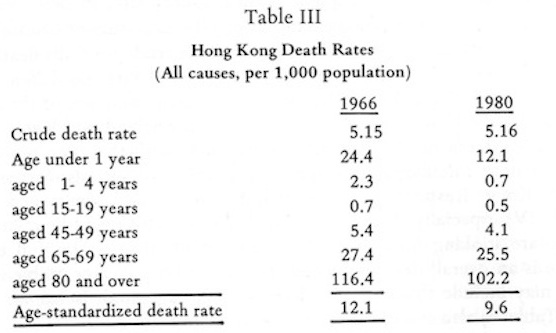

I would like to return to some of Farr's ideas. He investigated geographical variations in deaths and introduced the idea of age-specific death rates which are vital for comparisons if the populations of the different areas are made up of a different mixture of the various ages - obviously older people have higher death rates, He calculated 'expected'

deaths for different areas. He also looked at variations in deaths related to food supplies.

In London in the years of the mid-eighteenth century there was a very high correlation between the price of wheat and the number of burials - the more expensive the wheat, the greater the number of deaths. Farr's ideas are still used in Britain and in Hong Kong today and the same sorts of problems are found. Deaths from Bronchitis in England and Wales in 1970-72 were greater in the north than in the south but in every region unskilled workers (social class V) had higher rates than professional workers (social class I) with a gradient for the other occupational classes. Accidents in men showed a similar gradient, while in the children of men from the different occupational classes the same phenomenon existed for accidents, pneumonia and many other diseases.

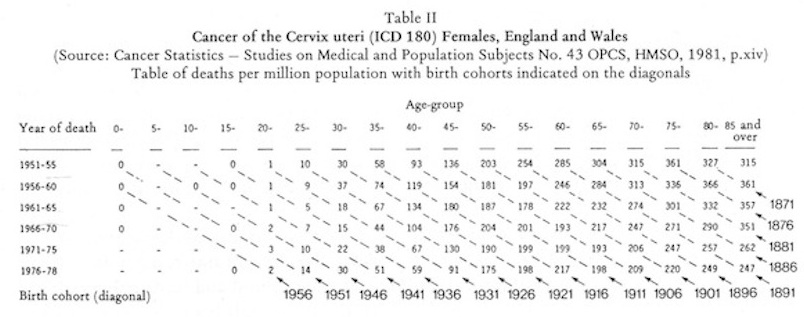

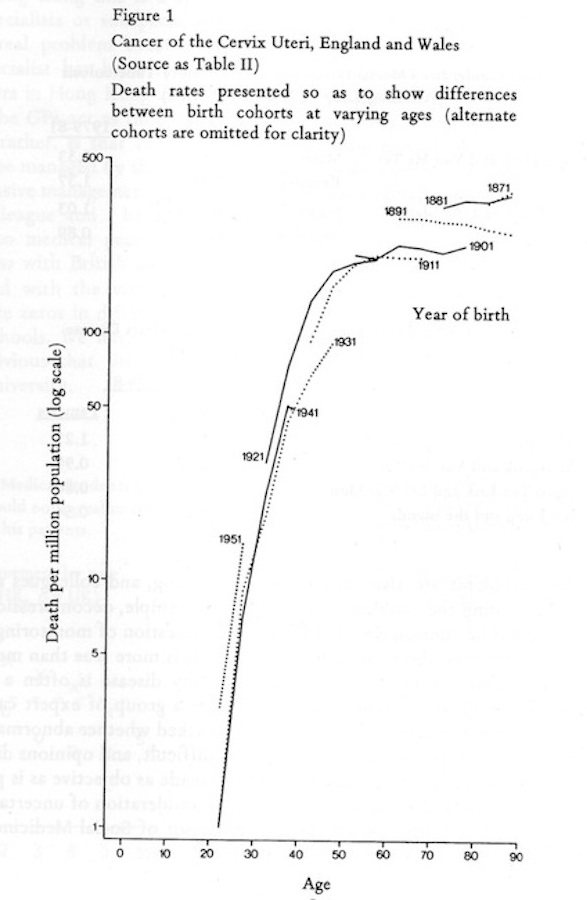

Large numbers of numbers are bread and butter for the epidemiologist, Table II shows death rates at various age groups at various time periods for cancer of the cervix in women in England and Wales.